So, you’re using Team Foundation Version Control (TFVC). You know about Team Projects and Collections, have a “stable” and “dev” branch for most projects, know how to do basic merges, and know how to shelve and unshelve changes. But you only have superficial knowledge of Git.

Well, then you’ve come to the right place: my Git intro for TFVC users.

Disclaimers

Here’s a heads-up about this particular post:

- It is not in-depth;

- It will oversimplify things to the point where not every statement is technically true;

- It does not teach you actual Git skills or commands;

- It is somewhat subjective.

Oh, and in my humble opinion: Git has a crazy learning curve. So buckle up!

And, as a final disclaimer: I’m writing this because I want to be able to explain the basics of Git, and certainly not because I’m an expert. In fact, I know more about Mercurial than about Git, I have worked mostly with TFVC in the past year, and would have to look up nearly every Git command when using the command line (I prefer GUI tools most of the time). Just so you know.

Disclaimers done, let’s get started!

On “TFS” vs “TFVC”

First, let’s get the TF* terminology right. These terms are different but related things:

- “TFVC” stands for Team Foundation Version Control, and is the actual system for keeping history of your codebase;

- “TFS” stands for Team Foundation Server and is the “environment” (if you will) in which source control features come together.

Many people, myself included, often use the acronym “TFS” when we actually mean “TFS with TFVC”. This is probably because TFS is very often used with TFVC as the version control system; but note that you can also use Git with TFS.

This blog post focuses on TFVC (which almost always implies you’re using TFS too).

Why Learn about git?

The personal reasons for learning Git are quite simple: it’s the de facto standard for version control. Knowing about Git is:

- crucial for your career (your new employer is likely to use Git);

- crucial for talking to new hires (who will very likely know Git);

- crucial for efficiently navigating open source.

The intrinsic reasons for learning Git all come down to the fact that it is insanely powerful (which also accounts for the steep learning curve). After having worked with TFVC in a 12 person team for over a year, I’d like to highlight the following main- and most direct advantages over TFVC:

- Cheap branching;

- Small repository size;

- Local commits;

- Better options for “shelving”;

- Speed;

- Better “offline” support.

Beyond these advantages, which you’ll get if you’re using a “central” Git repository, there are even more goodies if you tap into the distributed nature of Git, as well as the more powerful commands (e.g. to rewrite history).

Basic differences

Git is a lot like TFVC, in that it is also a Version Control System (VCS). It is also quite different. Here’s how they compare when managing the code base and doing changes:

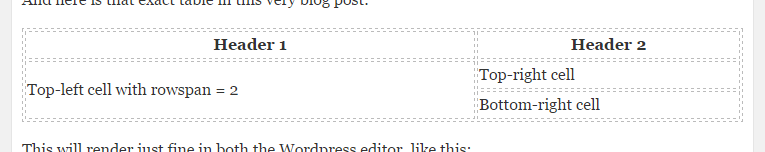

| TFVC |

Git |

| There is a central, server-hosted Team Project and you’ll have one or more local workspaces containing a copy of all the code. |

For now, let’s assume that there is a central repository hosted somewhere on a server. You’ll have one or more local “clone” repositories containing a copy of all the code and also all of its history. |

| A check in is a command to send your pending local changes to the server where they will be committed to the version control history. |

You commit changes locally which creates a “change set” private to your “clone”. You can do this multiple times. You push one or more change sets at once to the central repository. |

| You can Get the Latest Version from the server which directly tries to merge with your current state. |

You fetch changes from the central repository and merge with your current state (or do both at once by doing a pull) possibly creating a new commit. |

The fact that a TFVC “check in” is multiple separate commands in Git gives several advantages:

- You can build history in small, individual steps (commits), which you can undo individually in several ways, and you can apply individual commits to other branches.

- Your changes are “safe” in commits when you want to send your changes to the central repository and find out others have conflicting changes, by default they won’t get “lost” if merges go bad. With TFVC, you’re required to resolve conflicts as you try to check in, which can screw up “unsaved” changes.

Our next set of differences would be about branching, but before that it’s good to talk briefly about “shelving” changes.

Setting changes aside

With TFVC you can shelve changes you currently have to safeguard them, optionally reverting those changes in your local workspace. You don’t necessarily need to do this when switching work to another branch, because the branch is typically a sibling folder of the main branch. More on that later.

With Git, you can stash changes you currently have, reverting changes in your local clone. You have to do this before switching to another branch. In order to see how that works, let me move on to the next topic: branches.

Branches

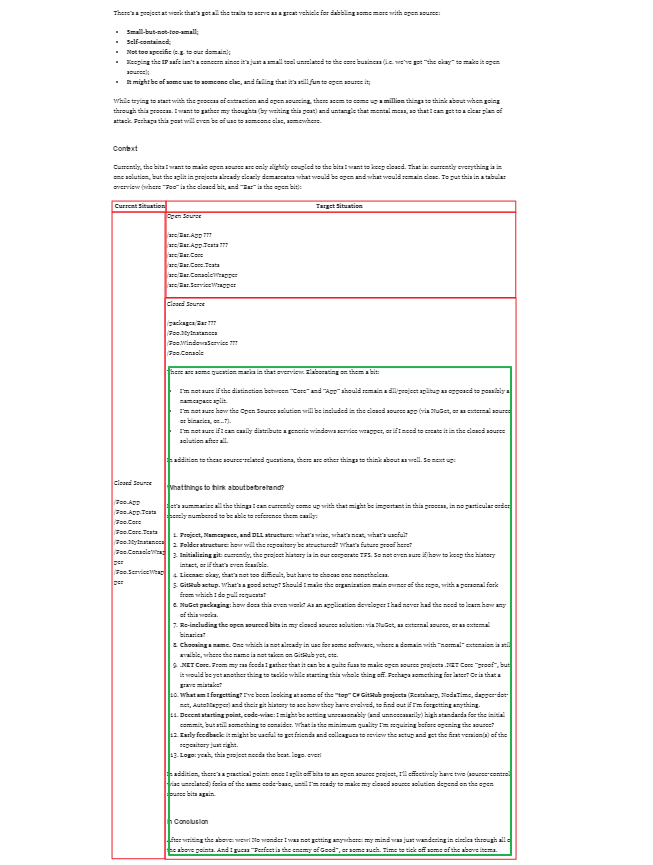

A typical setup in TFVC starts like this (with a local workspace matching the Team Project 1-on-1 in this example):

|

|

c:\project-x\main\all-code-goes-here |

Inside the project folder for the Team Project, there immediately is a sub folder called “main”. This is done so that it is easy to branch off the entire codebase for that project into this:

|

|

c:\project-x\dev\copy-of-all-code |

The folder “dev” is now a complete copy of “main”. This also means you could be working on two branches simultaneously, and you can check in files to both branches at ones if you so desire. You could even have “main” and “dev” at different points in your version control history.

Git is different.

With Git, the “main” folder as you’d have it in TFVC would be pointless. Instead, there is just:

|

|

c:\project-x\all-code-goes-here |

You can “branch off” any state of “project-x” at any point in time. Your folder “project-x” will point at a certain state, de facto having the code for a specific branch.

If you would like to have both branches “ready for action” on your disk, you would typically have multiple “clones” of the repository. One would be at the most recent state of the “main” (typically called “master”) branch, and another might be at the most recent state of another branch.

As a summary, Git branches relative to TFVC branches:

- Are light-weight and can be used to “switch context” for example to work on a feature;

- Are a top-level thing, as opposed to the “path-based” branches in TFVC;

- Allow for more precise merges and “cherry picking” of commits;

These differences allow for completely different workflows with Git. This is a topic for another post though, if you’re interested I’d recommend research things like “Git Flow”, “GitHub Flow”, and “GitLab Flow”.

Other differences

While there are many other differences, both small (e.g. specific commands) and big (e.g. the “distributed” nature of Git), this post will keep it at the above. Mentioned differences are in my opinion the most “direct” and eye-catching differences. If you want to learn about the other differences I recommend you first get started with some practical skills, e.g. by following a tutorial.

Conclusion

TFVC is a mature, decent version control system. But personally, having worked with both centralized and distributed version control, in TFVC I’m misssing:

- Ability to do commits locally;

- Cheap, more powerful branching;

- Great “shelve” options;

Those three, in addition to its “distributed” nature enabling online platforms like GitHub to flourish, are likely the reasons Git is so popular nowadays. In my opinion those are great intrinsic reasons to learn Git when you’re currently using TFVC (even if you cannot switch on the short term), and if not for those reasons then because it’s crucial for your career.

So ready yourself for a bad-ass learning-curve climb, and start learning more about Git!

Resources & Further Reading

Here are some links to continue your journey: